The first horror film I ever saw at age eight, indeed the first film I ever saw in a theater, was the 1959 House on Haunted Hill. It starred Vincent Price, and I now know it was directed by William Castle, called “the poor man’s Hitchcock,” who churned out many “B” thriller movies. Although Castle’s genre was the psychological thriller, his films are subgenres of horror. House on Haunted Hill was projected in “Emergo”, one of the gimmicks Castle was known for. In this case it meant that a large fluorescent inflatable skeleton drifted above the audience in some theaters during a scene when a skeleton rises from a vat to pursue the depraved wife of Price’s character. I have no memories of a skeleton in the movie theater, but who can forget Vincent Price’s voice? I also remember a woman laying on a table and a huge knife coming through her chest from beneath.

I should note that this was on Christmas day when my sailor dad was home on leave and to make us happy he let us choose from the newspaper what movie we wanted to see. My younger brother and I chose this film while my dad and older brother went to see DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. My mother was not pleased. William Castle later produced Rosemary’s Baby (1968), the psychological horror film directed by Roman Polanski.

Although I have no particular liking for the horror genre, people have strong opinions about these films. Some appreciate and even like horror while others may dislike all horror or some subgenre expressions of it. This article will argue that horror is a legitimate film genre, and that horror films have a Catholic Christian core and are accessible to a universal, that is, small “c” catholic audience. I will ask if the horror genre and many of its subgenres explore Christian theology and the human reality in relation to the divine and demonic or evil, so as to suggest or reinforce faith in God and hope? Likewise, is the horror genre catholic in the small “c” sense in ways that reveal the dignity and truth of the human person with free will, and engage and perhaps assuage human fear? I contend that horror films attempt to exploit human issues and create a confrontation between human and supernatural strengths and weaknesses and draw from and/or reinforce Catholic Christian theology. And this, all the while, as Alfred Hitchcock used to say, scaring the hell out of audiences.

The Genre and Sub-genres

There are many subgenres or overlapping genres to horror, from grindhouse (raw, explicitly violent, and gorey) to science fiction and aliens, to gothic (e.g. Hammer horror films from the UK), to vampires and even humorous undead horror such as the 2004 Shaun of the Dead about a young salesman who has no focus in life and has to cope with relatives, family, friends, and a zombie attack and infestation. An Iraq war veteran told me that this was the movie his unit watched over and over during down time. I asked why, and he shrugged his shoulders and said, “I don’t know. It’s funny, and we all liked it. It got us out of there for awhile.” Sometimes I wonder if it was more than this, that maybe the movie was a metaphor for their lives and how they saw and experienced the situation in which they found themselves: isolated, out of control, fearful, and chaotic.

In 1995 the Vatican published a list of “Important Films” marking the 100th anniversary of cinema. Under the category of “art,” F. W. Murnau’s silent vampire horror classic Nosferatu: a Symphony of Horror is listed. It is an adaptation of the 1897 novel Dracula by the Irish author Bram Stoker. Christians will recognize theological elements throughout the film but some think it is more haunting than scary.

Peter Malone, MSH, a Bible scholar and film critic (and Reel Spirituality contributor), distinguishes between horror films and terror films. “Of course, there is terror in horror films, but there are many thrillers that sometimes are described as horror whereas they are simply, as director Blake Edwards once titled a film, ‘An Experiment in Terror.’ Audiences identify with characters who are afraid, are being menaced or find themselves in life-threatening situations…. Many of the monster (as in cannibals) movies like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre franchise are not so much horror as extreme terror and unnaturally natural. Horror films are more than this, more than simply scary movies, no matter how sophisticated the craft and plot.”

And then there are the paranormal, supernatural, psychological and satanic subgenres in horror as well. These are often classified as drama or psychological thrillers, but if you look closely, these films, as with intentional horror movies, contain certain common conventions and visual and aural motifs (that when poorly used are nothing more than clichés) that evoke fear in the film and the audience and propel the action. Finally, for a horror film to work, the audience has to be able to identify with a character or situation.

Conventions

Formulaic Motifs

On CBS Sunday morning on June 30, 2013, the horror-meister himself, author and screenwriter Stephen King, spoke about what he likes about horror in an interview about his book Under the Dome now a current television series: “I liked the idea that things would get out of control and somebody would battle to put back control into their lives.” I have seen the first episode of Under the Dome and it already ticks off almost ever convention and motif listed above. And it is quite watchable.

Here are analyses of The Passion of the Christ, categorized as an “epic drama,” and the 2013 “psychological thriller” The Conjuring, both of which I contend are actually horror films that explore and to a certain extent reveal Catholic Christian theology while appealing to a broad audience.

The Passion of the Christ

When Mel Gibson’s 2004 genre-bending The Passion of the Christ was released, I noted in what turned out to be a controversial review that it was actually a horror film because it contained all the elements and many of the visual motifs noted above.

Think of the last week of Jesus’ (Jim Caviezel) life, especially that last Thursday and Friday. Christ in the darkness of the garden, when he goes to pray and sweat blood – alone. He is arrested and taken away, and falls, or is pushed, off the bridge and dangles there. There is the androgynous Satanic creature (Rosalinda Celentano) with worms crawling out of its nose and its ability to move about without constraints of nature, the grotesque infant it carries around, the heartbreak of Jesus’ mother Mary (Maia Morgenstern) and her inability to do anything to save her son, the extreme blood-letting of Jesus at the scourging, the contorted grotesque faces of two children taunting Judas (Luca Lionello), Judas’ suicide and his body hanging over the putrid corpse of a lamb, the crows who peck the eyes out of the two thieves who were crucified with Jesus, Satan screaming, the drop of rain that causes the earthquake and damage to the temple.

The Passion of the Christ expresses horror, chaos in the universe, Jesus’ isolation, vulnerability, betrayal, pain and ultimately restoration because the Father loves the Son who rises from the dead overcoming death, sin, and the devil forever. In The Passion of the Christ, Satan and God seem to be in contention over the son, Jesus. Christ is overwhelmed by the dark forces but ultimately triumphs. Jesus’ passion death and resurrection were to redeem us from sin, yes, but also to save us from suffering. This restoration of order, or regaining of control, marks the end of most horror movies and offers audiences a way to assuage their own fears. The sacramental is very evident in The Passion of the Christ, because the film is the external manifestation of immense internal and grace-filled realities.

The Conjuring

Real life husband and wife Ed (Patrick Wilson) and Lorraine (Vera Farmiga) Warren are a Catholic couple who believe that God brought them together for a reason, to work as demonologists and debunkers of the occult and demonic possession as called for in their investigations. Sometimes they report to a local priest to arrange for an exorcism. It’s the 1970s and they have already dealt with the paranormal in Amityville, New York (made into the 1979 film The Amityville Horror). They also have a museum of the occult that they keep so the creatures that possess them will not escape. They worry about their young daughter who wanders into the locked room and warn her away.

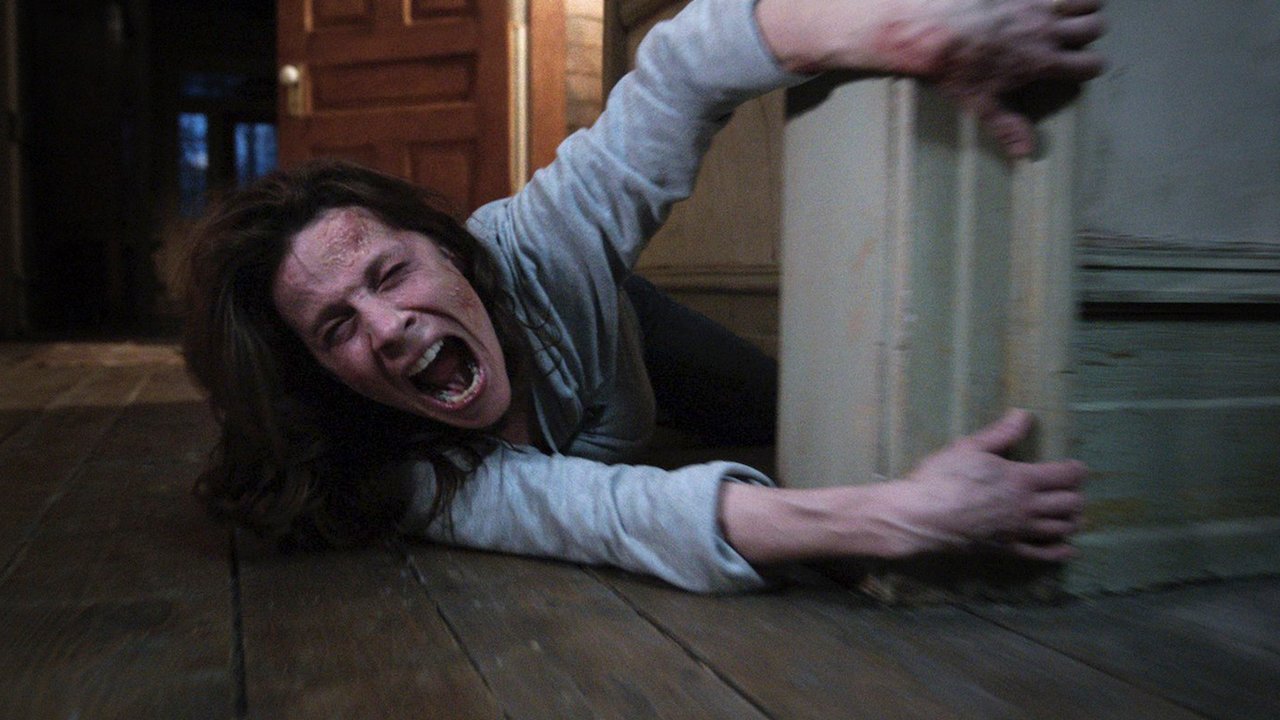

In Rhode Island, Roger (Ron Livingston) and Carolyn (Lili Taylor) move into an old isolated farmhouse with their five young daughters. Happy at first, they discover a hidden basement and an old clown toy that one of the girls keeps. It becomes a mirror to a ghost that the family discovers committed murder and suicide in the house and on the property decades before. The family dog is found butchered outside; birds crash into the windows and die. Then Carolyn develops bruises on her body, a funky smell at 3:07pm every night, one of the girls sleep walks, something is pulling at the children’s feet while they sleep, and it becomes evident that the house and family are being oppressed, obsessed, and finally Carolyn is possessed.

Roger approaches Ed who investigates, but doesn’t want to involve Lorraine if he can help it because she feels things too intensely. Eventually, with an assistant and a sheriff’s deputy, they set up their equipment and actually film something that they show a priest. While he is requesting permission to do an exorcism, Ed and Lorraine ask Roger if the children have been baptized. He replies that they never got around to it, and this lack of baptism causes the Warrens to pause. Why? Though not in the film, the obvious reason is that when a child is baptized the godparents reject Satan in the name of the child, until they can profess this themselves. Things get so bad that Ed brings crucifixes to the house and then holding a cross, carries out the exorcism himself.

The Conjuring has all the motifs and themes of a satanic horror film in the manner of The Exorcist and The Exorcism of Emily Rose so calling it a psychological thriller does not do it justice. It is extremely scary and evokes much horror and manages to say something theological despite its inaccurate historical facts about the Salem Witch Trials and the fact that no bishop in his right mind would allow a layman to carry out an exorcism without permission. Properly trained lay people can, however, assist in exorcisms and recite prayers of deliverance outside of an exorcism. In my research for this article, I learned that the Catholic Church does not officially recognize demonologists though it is known that at least one bishop has consulted one.

The picture of the two married couples in the film is a very positive one, and the sacrament of Baptism as necessary for salvation, spiritual well being and source of grace, is reinforced without scaring a viewer into it. What’s creepy is the museum that the Warren’s maintain. I would have hoped for more involvement of an exorcist in the film because he would have used the rite of exorcism to free even objects of the devil by casting them to the Cross of Christ.

As with The Passion of the Christ, The Conjuring has all the conventions and motifs of horror (and both have “R” ratings, by the way). While The Passion may have brought us to tears, The Conjuring brings out our screams, of this I am sure. Both films meet the requirements for a Catholic and a catholic audience.

The C(c)atholic Audience

“Moving beyond the realms of ordinary experiences,” notes Peter Malone, “beyond the natural means that we are involved with are horrifying stories that transcend the natural. Catholics and all Christians, can begin feeling comfortable about the religious dimensions of horror when we start to speak about transcendence.”

Malone continues: “Horror comes from threat and menace beyond the natural. The sources of horror are not readily explained rationally (whereas terror films can be.) We share the terror but are aghast at the horror. Audiences relish the tantalizing attraction of, at least for the running time of the film, having a Darth Vader experience of going over to the dark side. Anyone who refuses to acknowledge the dark side becomes its victim – and there is a great danger of rigid individuals and groups, who, as was once said, have (and demand that others have) a Pollyanna approach to life: a sunny denial of evil in the world, and a potential to be scandalized and shocked at finding it in themselves.”

Many Christians that I know, whether Catholic or Protestant, believe that horror films are immoral because they often receive an “R” rating from the MPAA. First of all, film ratings from the Motion Picture Association of America are not moral judgments on a film but are offered as an age-appropriate content guide for parents. When people boast to me that they have never seen an “R” rated movie, I think they must have made a deal with Peter Pan to never grow up.

The reviews that come from the Catholic News Service (formerly the Office for Film and Broadcast of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops) provide moral judgment on a film through its ratings (usually by a solo reviewer), but do not address what the movie means.

Ratings are helpful guides, perhaps, but these do not take away the responsibility of the audience to be critically autonomous and to choose according to one’s beliefs and values and, once a film is chosen, to reflect and discover what the movie means to you.

I asked filmmaker Scott Derrickson (Constantine, The Exorcism of Emily Rose, Sinister) for his thoughts about why some Christians think horror films are immoral. His response: “Anyone who finds horror cinema fundamentally immoral either doesn’t watch it, or doesn’t understand it. It’s perfectly fine to say that you don’t like the genre; that you don’t like to be scared by movies – but if you are wise, you will respect it. In my experience, the instinct to judge the horror genre often comes from people who don’t strive to confront their own fears. Many who choose only positive art and entertainment will judge horror as immoral, because to them, it feels wrong to confront the severe darkness that is in ourselves and in the world. Horror is too challenging for them. It is the genre of non-denial.”

Craig Detweiller, film professor at Pepperdine University, said, “It is easy to see why bloodletting and torture are repugnant to many moviegoers. The worst horror films revel in bloodlust and engage in a fetishism of evil. Yet, there is plenty of violence and horror in the Bible. The apocalyptic images in scripture remind us that sometimes it takes strong, prophetic visions to wake us from our slumber. Horror at its best offer a cautionary tale designed to shock us into self-recognition.”

Wes Craven, raised in a strict Baptist family, is the master of the horror genre and it is worth reading what he is quoted as saying in an essay by Craig Detweiller in 2006: “When I first wrote A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), I was trying to account for something in human nature, in the human race, that had been here since day one and went all the way back to Cain and Abel, one half of humanity rising up to club the other running right up to events in the world today…. We have to be aware that within the pure hero is the potential to be a real villain and within any villain there is the capacity for elements of humor, tenderness, vulnerability and love.”

Craven did not get his desired ending in Nightmare: “In my version, the film ended with Nancy turning her back on Freddy and telling him he was nothing. It showed that evil can be confronted and diminished. That ending was very carefully thought through and had to do with a worldview of my own.” Instead, the ending was changed to introduce a sequel, something we are quite used to now.

I was present at the City of Angels Film Festival in 2006 when Scott Derrickson interviewed Wes Craven. Scott asked the famed director why people go to horror movies. Craven replied that they watch horror because they are already afraid and in a film there is a beginning, a middle and an end so people can, through the experiences of the characters, mitigate their own fears and see that they can have control of the chaos in their lives.

Let me know if you think I made a good case for horror films being Catholic, with a big “C” and a little “c”. Let the conversation begin.

The first horror film I ever saw at age eight, indeed the first film I ever saw in a theater, was the 1959 House on Haunted Hill. It starred Vincent Price, and I now know it was directed by William Castle, called “the poor man’s Hitchcock,” who churned out many “B” thriller movies. Although Castle’s genre was the psychological thriller, his films are subgenres of horror. House on Haunted Hill was projected in “Emergo”, one of the gimmicks Castle was known for. In this case it meant that a large fluorescent inflatable skeleton drifted above the audience in some theaters during a scene when a skeleton rises from a vat to pursue the depraved wife of Price’s character. I have no memories of a skeleton in the movie theater, but who can forget Vincent Price’s voice? I also remember a woman laying on a table and a huge knife coming through her chest from beneath.

I should note that this was on Christmas day when my sailor dad was home on leave and to make us happy he let us choose from the newspaper what movie we wanted to see. My younger brother and I chose this film while my dad and older brother went to see DeMille’s The Ten Commandments. My mother was not pleased. William Castle later produced Rosemary’s Baby (1968), the psychological horror film directed by Roman Polanski.

Although I have no particular liking for the horror genre, people have strong opinions about these films. Some appreciate and even like horror while others may dislike all horror or some subgenre expressions of it. This article will argue that horror is a legitimate film genre, and that horror films have a Catholic Christian core and are accessible to a universal, that is, small “c” catholic audience. I will ask if the horror genre and many of its subgenres explore Christian theology and the human reality in relation to the divine and demonic or evil, so as to suggest or reinforce faith in God and hope? Likewise, is the horror genre catholic in the small “c” sense in ways that reveal the dignity and truth of the human person with free will, and engage and perhaps assuage human fear? I contend that horror films attempt to exploit human issues and create a confrontation between human and supernatural strengths and weaknesses and draw from and/or reinforce Catholic Christian theology. And this, all the while, as Alfred Hitchcock used to say, scaring the hell out of audiences.

The Genre and Sub-genres

There are many subgenres or overlapping genres to horror, from grindhouse (raw, explicitly violent, and gorey) to science fiction and aliens, to gothic (e.g. Hammer horror films from the UK), to vampires and even humorous undead horror such as the 2004 Shaun of the Dead about a young salesman who has no focus in life and has to cope with relatives, family, friends, and a zombie attack and infestation. An Iraq war veteran told me that this was the movie his unit watched over and over during down time. I asked why, and he shrugged his shoulders and said, “I don’t know. It’s funny, and we all liked it. It got us out of there for awhile.” Sometimes I wonder if it was more than this, that maybe the movie was a metaphor for their lives and how they saw and experienced the situation in which they found themselves: isolated, out of control, fearful, and chaotic.

In 1995 the Vatican published a list of “Important Films” marking the 100th anniversary of cinema. Under the category of “art,” F. W. Murnau’s silent vampire horror classic Nosferatu: a Symphony of Horror is listed. It is an adaptation of the 1897 novel Dracula by the Irish author Bram Stoker. Christians will recognize theological elements throughout the film but some think it is more haunting than scary.

Peter Malone, MSH, a Bible scholar and film critic (and Reel Spirituality contributor), distinguishes between horror films and terror films. “Of course, there is terror in horror films, but there are many thrillers that sometimes are described as horror whereas they are simply, as director Blake Edwards once titled a film, ‘An Experiment in Terror.’ Audiences identify with characters who are afraid, are being menaced or find themselves in life-threatening situations…. Many of the monster (as in cannibals) movies like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre franchise are not so much horror as extreme terror and unnaturally natural. Horror films are more than this, more than simply scary movies, no matter how sophisticated the craft and plot.”

And then there are the paranormal, supernatural, psychological and satanic subgenres in horror as well. These are often classified as drama or psychological thrillers, but if you look closely, these films, as with intentional horror movies, contain certain common conventions and visual and aural motifs (that when poorly used are nothing more than clichés) that evoke fear in the film and the audience and propel the action. Finally, for a horror film to work, the audience has to be able to identify with a character or situation.

Conventions

Formulaic Motifs

On CBS Sunday morning on June 30, 2013, the horror-meister himself, author and screenwriter Stephen King, spoke about what he likes about horror in an interview about his book Under the Dome now a current television series: “I liked the idea that things would get out of control and somebody would battle to put back control into their lives.” I have seen the first episode of Under the Dome and it already ticks off almost ever convention and motif listed above. And it is quite watchable.

Here are analyses of The Passion of the Christ, categorized as an “epic drama,” and the 2013 “psychological thriller” The Conjuring, both of which I contend are actually horror films that explore and to a certain extent reveal Catholic Christian theology while appealing to a broad audience.

The Passion of the Christ

When Mel Gibson’s 2004 genre-bending The Passion of the Christ was released, I noted in what turned out to be a controversial review that it was actually a horror film because it contained all the elements and many of the visual motifs noted above.

Think of the last week of Jesus’ (Jim Caviezel) life, especially that last Thursday and Friday. Christ in the darkness of the garden, when he goes to pray and sweat blood – alone. He is arrested and taken away, and falls, or is pushed, off the bridge and dangles there. There is the androgynous Satanic creature (Rosalinda Celentano) with worms crawling out of its nose and its ability to move about without constraints of nature, the grotesque infant it carries around, the heartbreak of Jesus’ mother Mary (Maia Morgenstern) and her inability to do anything to save her son, the extreme blood-letting of Jesus at the scourging, the contorted grotesque faces of two children taunting Judas (Luca Lionello), Judas’ suicide and his body hanging over the putrid corpse of a lamb, the crows who peck the eyes out of the two thieves who were crucified with Jesus, Satan screaming, the drop of rain that causes the earthquake and damage to the temple.

The Passion of the Christ expresses horror, chaos in the universe, Jesus’ isolation, vulnerability, betrayal, pain and ultimately restoration because the Father loves the Son who rises from the dead overcoming death, sin, and the devil forever. In The Passion of the Christ, Satan and God seem to be in contention over the son, Jesus. Christ is overwhelmed by the dark forces but ultimately triumphs. Jesus’ passion death and resurrection were to redeem us from sin, yes, but also to save us from suffering. This restoration of order, or regaining of control, marks the end of most horror movies and offers audiences a way to assuage their own fears. The sacramental is very evident in The Passion of the Christ, because the film is the external manifestation of immense internal and grace-filled realities.

The Conjuring

Real life husband and wife Ed (Patrick Wilson) and Lorraine (Vera Farmiga) Warren are a Catholic couple who believe that God brought them together for a reason, to work as demonologists and debunkers of the occult and demonic possession as called for in their investigations. Sometimes they report to a local priest to arrange for an exorcism. It’s the 1970s and they have already dealt with the paranormal in Amityville, New York (made into the 1979 film The Amityville Horror). They also have a museum of the occult that they keep so the creatures that possess them will not escape. They worry about their young daughter who wanders into the locked room and warn her away.

In Rhode Island, Roger (Ron Livingston) and Carolyn (Lili Taylor) move into an old isolated farmhouse with their five young daughters. Happy at first, they discover a hidden basement and an old clown toy that one of the girls keeps. It becomes a mirror to a ghost that the family discovers committed murder and suicide in the house and on the property decades before. The family dog is found butchered outside; birds crash into the windows and die. Then Carolyn develops bruises on her body, a funky smell at 3:07pm every night, one of the girls sleep walks, something is pulling at the children’s feet while they sleep, and it becomes evident that the house and family are being oppressed, obsessed, and finally Carolyn is possessed.

Roger approaches Ed who investigates, but doesn’t want to involve Lorraine if he can help it because she feels things too intensely. Eventually, with an assistant and a sheriff’s deputy, they set up their equipment and actually film something that they show a priest. While he is requesting permission to do an exorcism, Ed and Lorraine ask Roger if the children have been baptized. He replies that they never got around to it, and this lack of baptism causes the Warrens to pause. Why? Though not in the film, the obvious reason is that when a child is baptized the godparents reject Satan in the name of the child, until they can profess this themselves. Things get so bad that Ed brings crucifixes to the house and then holding a cross, carries out the exorcism himself.

The Conjuring has all the motifs and themes of a satanic horror film in the manner of The Exorcist and The Exorcism of Emily Rose so calling it a psychological thriller does not do it justice. It is extremely scary and evokes much horror and manages to say something theological despite its inaccurate historical facts about the Salem Witch Trials and the fact that no bishop in his right mind would allow a layman to carry out an exorcism without permission. Properly trained lay people can, however, assist in exorcisms and recite prayers of deliverance outside of an exorcism. In my research for this article, I learned that the Catholic Church does not officially recognize demonologists though it is known that at least one bishop has consulted one.

The picture of the two married couples in the film is a very positive one, and the sacrament of Baptism as necessary for salvation, spiritual well being and source of grace, is reinforced without scaring a viewer into it. What’s creepy is the museum that the Warren’s maintain. I would have hoped for more involvement of an exorcist in the film because he would have used the rite of exorcism to free even objects of the devil by casting them to the Cross of Christ.

As with The Passion of the Christ, The Conjuring has all the conventions and motifs of horror (and both have “R” ratings, by the way). While The Passion may have brought us to tears, The Conjuring brings out our screams, of this I am sure. Both films meet the requirements for a Catholic and a catholic audience.

The C(c)atholic Audience

“Moving beyond the realms of ordinary experiences,” notes Peter Malone, “beyond the natural means that we are involved with are horrifying stories that transcend the natural. Catholics and all Christians, can begin feeling comfortable about the religious dimensions of horror when we start to speak about transcendence.”

Malone continues: “Horror comes from threat and menace beyond the natural. The sources of horror are not readily explained rationally (whereas terror films can be.) We share the terror but are aghast at the horror. Audiences relish the tantalizing attraction of, at least for the running time of the film, having a Darth Vader experience of going over to the dark side. Anyone who refuses to acknowledge the dark side becomes its victim – and there is a great danger of rigid individuals and groups, who, as was once said, have (and demand that others have) a Pollyanna approach to life: a sunny denial of evil in the world, and a potential to be scandalized and shocked at finding it in themselves.”

Many Christians that I know, whether Catholic or Protestant, believe that horror films are immoral because they often receive an “R” rating from the MPAA. First of all, film ratings from the Motion Picture Association of America are not moral judgments on a film but are offered as an age-appropriate content guide for parents. When people boast to me that they have never seen an “R” rated movie, I think they must have made a deal with Peter Pan to never grow up.

The reviews that come from the Catholic News Service (formerly the Office for Film and Broadcast of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops) provide moral judgment on a film through its ratings (usually by a solo reviewer), but do not address what the movie means.

Ratings are helpful guides, perhaps, but these do not take away the responsibility of the audience to be critically autonomous and to choose according to one’s beliefs and values and, once a film is chosen, to reflect and discover what the movie means to you.

I asked filmmaker Scott Derrickson (Constantine, The Exorcism of Emily Rose, Sinister) for his thoughts about why some Christians think horror films are immoral. His response: “Anyone who finds horror cinema fundamentally immoral either doesn’t watch it, or doesn’t understand it. It’s perfectly fine to say that you don’t like the genre; that you don’t like to be scared by movies – but if you are wise, you will respect it. In my experience, the instinct to judge the horror genre often comes from people who don’t strive to confront their own fears. Many who choose only positive art and entertainment will judge horror as immoral, because to them, it feels wrong to confront the severe darkness that is in ourselves and in the world. Horror is too challenging for them. It is the genre of non-denial.”

Craig Detweiller, film professor at Pepperdine University, said, “It is easy to see why bloodletting and torture are repugnant to many moviegoers. The worst horror films revel in bloodlust and engage in a fetishism of evil. Yet, there is plenty of violence and horror in the Bible. The apocalyptic images in scripture remind us that sometimes it takes strong, prophetic visions to wake us from our slumber. Horror at its best offer a cautionary tale designed to shock us into self-recognition.”

Wes Craven, raised in a strict Baptist family, is the master of the horror genre and it is worth reading what he is quoted as saying in an essay by Craig Detweiller in 2006: “When I first wrote A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), I was trying to account for something in human nature, in the human race, that had been here since day one and went all the way back to Cain and Abel, one half of humanity rising up to club the other running right up to events in the world today…. We have to be aware that within the pure hero is the potential to be a real villain and within any villain there is the capacity for elements of humor, tenderness, vulnerability and love.”

Craven did not get his desired ending in Nightmare: “In my version, the film ended with Nancy turning her back on Freddy and telling him he was nothing. It showed that evil can be confronted and diminished. That ending was very carefully thought through and had to do with a worldview of my own.” Instead, the ending was changed to introduce a sequel, something we are quite used to now.

I was present at the City of Angels Film Festival in 2006 when Scott Derrickson interviewed Wes Craven. Scott asked the famed director why people go to horror movies. Craven replied that they watch horror because they are already afraid and in a film there is a beginning, a middle and an end so people can, through the experiences of the characters, mitigate their own fears and see that they can have control of the chaos in their lives.

Let me know if you think I made a good case for horror films being Catholic, with a big “C” and a little “c”. Let the conversation begin.

Sister Rose Pacatte, FSP, is an American film critic and Catholic nun. In 1967, at age 15, Pacatte entered the Daughters of St. Paul, an order which conducts religious outreach through mass media.

Scott Derrickson, director and screenwriter of The Exorcism of Emily Rose and Doctor Strange, has a conversation about storytelling, the horror genre, and the creative process.