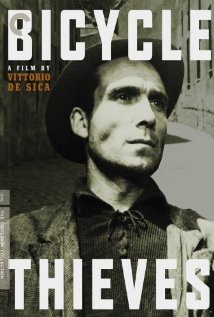

Italian Neorealism set out to show the people truthfully without any filmmaking glitz. These films use non-professional actors, shoot on location, and feature the more impoverished areas of Italy. (For instance, in Bicycle Thieves, we are in Rome, but it is not the Rome we see in Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant pictures.) These films want to show the plight of the poor as clearly as possible.

Italian Neorealism set out to show the people truthfully without any filmmaking glitz. These films use non-professional actors, shoot on location, and feature the more impoverished areas of Italy. (For instance, in Bicycle Thieves, we are in Rome, but it is not the Rome we see in Audrey Hepburn and Cary Grant pictures.) These films want to show the plight of the poor as clearly as possible.

Crash, on the other hand, is hyperreal. These are not characters – they’re characterizations meant to evoke certain stereotypes. The audience isn’t meant to identify with these tokens. We’re meant to identify them as examples of our prejudices. The movie then proceeds to both satisfy then subvert our expectations of how these stereotypes will interact.

I try very hard to log this movie, but it’s just so maudlin, so sentimental. I feel so manipulated. I felt the same way watching Bicycle Thieves. Even in a film which supposedly was emblematic of a new more real form of cinema, I always know I’m still watching a constructed narrative. It’s not real. Choices have been made to move me in a certain emotional and, I’d add, political direction.

These are both movies that are trying primarily to influence me to… something. I’m not sure what. Perhaps to care about people differently? But I don’t think they’re actually trying to make me act any differently. Maybe they are. I suppose the argument could be made that both Crash and Bicycle Thieves are saying to me, “If only you would learn to see that all people are the same, you’d treat everyone equally!” (Exclamation point.) I don’t buy it though, because they don’t actually propose any forward movement. They just ask me to sit there in the theater and feel sad.

Now, all that’s not to say that there isn’t any worth in these films. In the annals of film history, Bicycle Thieves and Italian Neorealism certainly deserve a couple of pages. The movement was a sharp break from the film style that preceded it and has been very influential. Crash won a few Oscars. Both movies attempt to typify their respective cities in their respective times, offering a broad sweeping look at life in Rome and L.A., albeit through very different methods – Bicycle Thieves through the experience of one man and his son and Crash through the experiences of an ensemble. And Bicycle Thieves and Crash each have their own areas of focus as well – poverty and racism, respectively.

Now, all that’s not to say that there isn’t any worth in these films. In the annals of film history, Bicycle Thieves and Italian Neorealism certainly deserve a couple of pages. The movement was a sharp break from the film style that preceded it and has been very influential. Crash won a few Oscars. Both movies attempt to typify their respective cities in their respective times, offering a broad sweeping look at life in Rome and L.A., albeit through very different methods – Bicycle Thieves through the experience of one man and his son and Crash through the experiences of an ensemble. And Bicycle Thieves and Crash each have their own areas of focus as well – poverty and racism, respectively.

Truly seeing our neighbors is important. Paying attention to their struggles and concerns is the first step toward sharing in those struggles with them, the first move toward actually helping them. And maybe that’s all we can really expect movies to do for us. Film is a visual medium, after all, and if a film truly shows its subject perhaps it has done its best work. But we can’t stop there because we live in the actual real world these movies are trying to represent.

There is an eschatology that purports that what we Christians really need is to go “back to the garden,” that the path of humanity is back to a pre-Fall state in the idealic Eden, as if all that has happened since has been wiped away. That’s not the path of scripture. That’s not consistent with the redemptive work of God. God redeems what’s broken. God doesn’t wipe it away. God integrates it into a perfect future.

So, in the Bible, we see the first city being built out of rebellion. God had told Cain that he’d always be unsettled because of his sin. Cain and his descendants build a city so they won’t have to wander over the face of the earth. They build a city for mutual protection instead of relying on protection by God. Then we see Babel and the disaster that results there when God comes down and scatters its inhabitants around the globe. Then there’s the flood, and humanity is almost completely wiped from the face of the earth. After the flood, God says that’s the last time God will wipe things away completely.

Then people begin building cities again, and Jerusalem, a city, soon becomes this emblem of God’s presence and protection of God’s people. During the Babylonian captivity, God tells the Israelites to pray for their city, for Babylon, and work for its benefit. Nehemiah and Ezra go back to Jerusalem and rebuild its walls. Jesus shows us and does most of his work in and around cities. Paul travels from city to city sharing the Gospel. And finally in Revelation, when we see heaven coming down out of the sky to be united to earth, its a city where God and man dwell together in peace. We started in a garden, built cities out of rebellion, but then God took our rebellious act and integrated it into God’s plan for all creation. By God’s will, cities are here to stay.

Furthermore, the world is being increasingly urbanized. In 1800, only 3% of the world’s population lived in urban areas. In 2008, for the first time in history, rural and urban populations were equal. By 2050, 70% of the world’s population is expected to live in urban areas. Increasingly, to be involved in the mission of God among God’s people is going to mean being involved in cities.

And we can’t simply care deeply about them. We are going to have to be involved in them. Love is not an emotion. Love is action. Love is feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, nursing the ill, and rehabilitating the criminals. Love is being good citizens, being civic-minded. Love is urban work. It is teaching in low-income schools and volunteering at YMCAs and attending city council meetings and joining neighborhood watch programs. Love is inviting your neighbors over for a BBQ and picking up trash left in your apartment complex hallways. Love is seeing and responding to needs we see in our urban environments with patient, kind, action.

So, I guess we can appreciate Bicycle Thieves and Crash for showing us needs, but it is our responsibility to take things a step further and get involved. As Christians we should be acting, not simply seeing.